Gaining the Ore

Around 1590 the Company of Mines Royal began work on the copper veins at Coniston. Early work was all carried out by hand. Brute force broke up the rock face, and tunnels were dug out very slowly. Only enough rock was removed to fit one person, and these access tunnels are called ‘coffin levels’ because of their distinct coffin-outline. A 17th century tunnel like Cobbler’s Level could still take three years to dig. The Elizabethan Company of Mines Royal was headed up by German experts from the Tyrol and Bavaria. Their mines penetrated the earth more than 180 feet below the surface. Work continued after the Civil War but perhaps not much.

Gunpowder was introduced at the end of the 17th century and this changed everything. Work was much faster and mines could go much deeper than before, now reaching over 300 feet below the surface. Charges were laid into a drill-hole in the rock using ‘jumper’, iron rods made on-site. You can still see hand-driven shot holes. Gunpowder was replaced by dynamite in 1877, and jumpers replaced by compressed-air drills in 1883.

Draining, Pumping and Ventilation

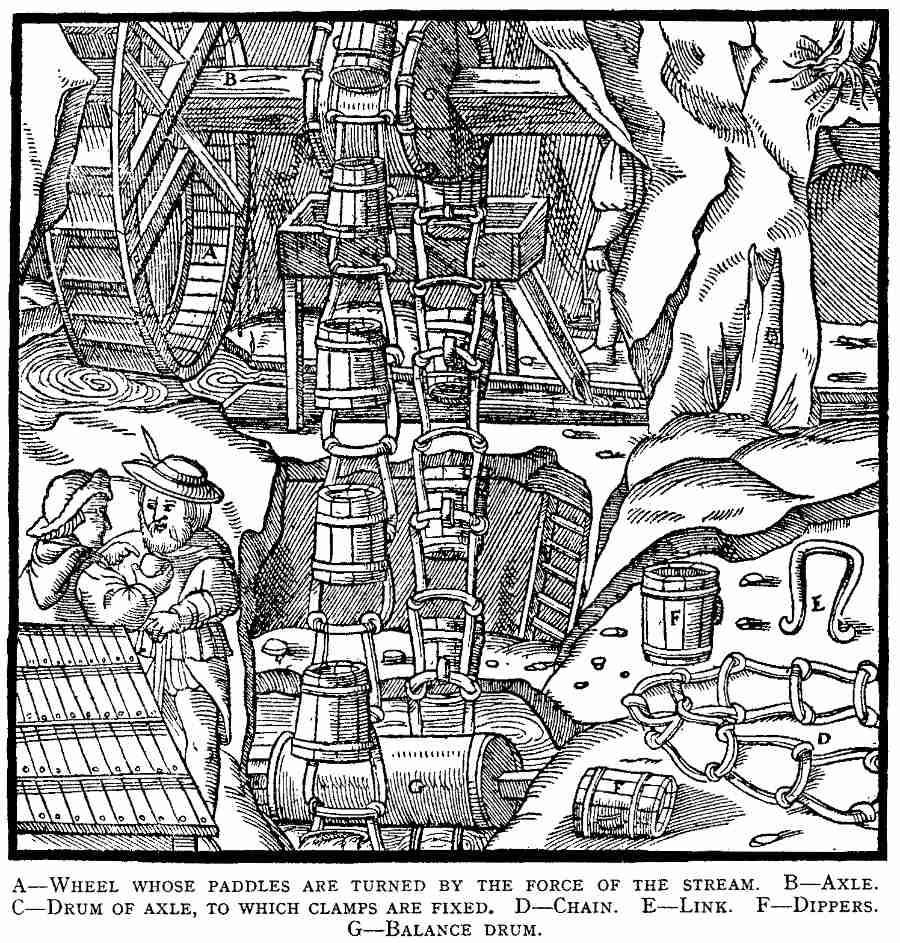

Rain and water in general are a miner’s enemies. Coniston is no exception. The copper mines occupy an extremely wet part of the Lake District. As early as 1602 the miners built walls around the violent Rough Beck to encourage it away from their working areas. Early miners might also have drained their tunnels using a ‘rag-and-chain’-type pump (see below for an illustration of a 16th example in Agricola's book De Re Metallica), or by hoisting buckets to the surface using a windlass.

As mines went deeper the problems multiplied. A waterwheel (the Bonsor East Wheel) was put to work in the 18th century, and Cobbler’s Level was also expanded. The waterwheel also winched ore to the surface.

Thriddle Incline was built in the 19th century to pump water from the Fleming, Taylor and Deep Levels. The rocking motion of a ‘balance bob’ drew up the water via a series of pump rods. The incline also wound ore up from the shaft. Power was provided first by Millican’s wheel at the Bonsor West Shaft, and then by the New Engine waterwheel built to replace it in the 1850s. Most of the pumping from Deep Level was carried out by the Old Engine Shaft Wheel, part of which still stands.

Poisonous and explosive gases and the lack of oxygen that characterize coal mines were not problems. The early copper miners may have complained of too much ventilation!

Once in the depths of the earth, ventilation shafts were all that was required to help the miners breathe, and to clear the working areas of dust clouds. There are many of these at Coniston, reflecting the underground routes of the mineral veins.

Transporting the Ore / Transportation

Early miners probably raised the ore on a jack-roll winch or a horse gin. By the 18th century it was raised in ‘kibbles’, or large buckets, and wooden tracks for moving ore about could be built into the tunnels, which were by now much larger.

Once above-ground, wheelbarrows, packhorses or carts were used. From the 18th century, wagons began to replace the horses and wheelbarrows.

During its 19th century heyday, a wooden tramway along Deep Level let miners put horses to work dragging the ores out from the workfaces. Deep Level, also called Horse Level, measured a mile-and-a-half including all its branches.

During processing, moving ore around the extremely-wet site was kept to a minimum. This was a big influence on how buildings were laid out over the years. It led to the construction of new buildings at Paddy End, for example, to process ores from close to Levers Water Beck. Ores from Middle Level were carried to the Paddy End Works along a shallow incline, on wagons powered by gravity. Paddy End Works eventually closed, by which time the Bonsor Mills received all the ores in horse-drawn wagons.

Some ores were transported along an aerial tramway - a rope suspended from stone pylons between Paddy End Middle Shaft and the dressing floors at the Bonsor Mills. Coniston’s would have been the longest continuous winding rope in the country.

Processing the ore

Early miners recovered high-quality ores which didn’t need much processing to become sellable. These were sent to ‘crushing huts’ almost as soon as they were retrieved. Remains of the huts can be found near the works from which they were recovered, as at Simon’s Nick.

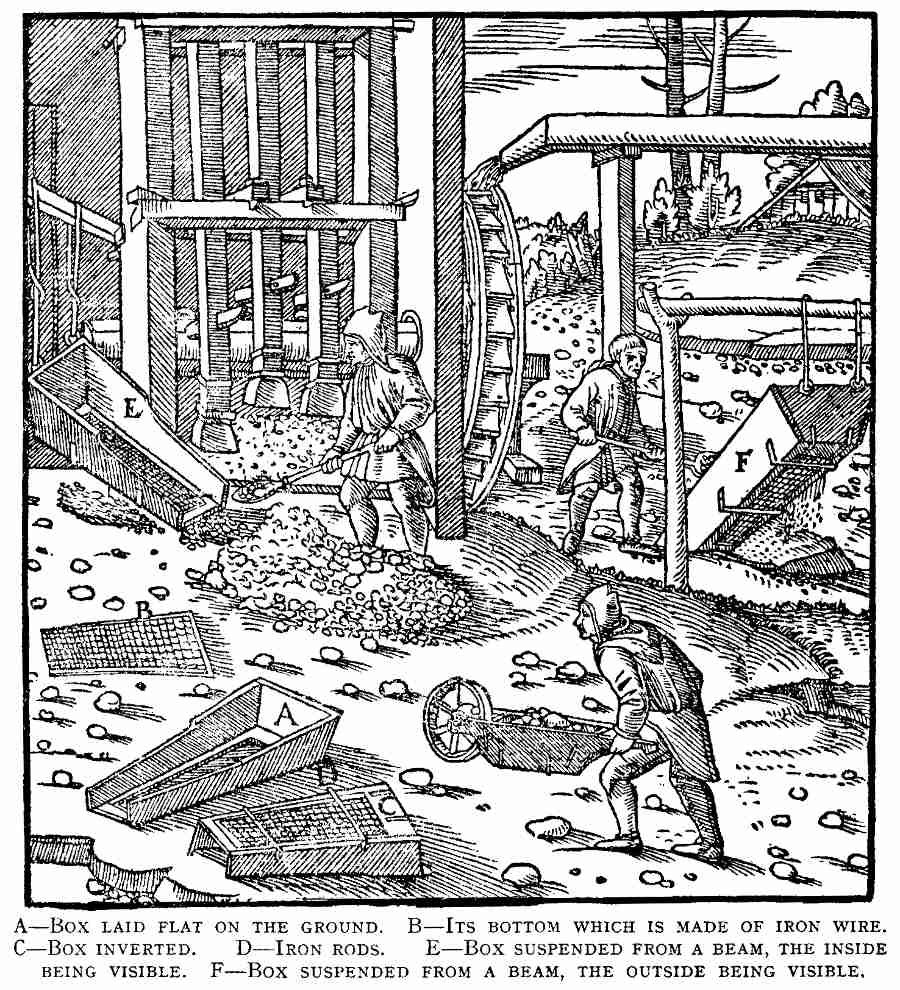

Ore of poorer quality needed more work. This was dressed and crushed in a stamp mill, a battery of four iron-shod timber beams, or ‘stamps’. Powered by a water wheel the stamps dropped alternately to crush the ore. Ore would be loaded into the mill from a hopper. One such mill is recorded working in Coniston by 1619, but we don’t know for sure where this was. An illustration of a 16th example is included in Agricola's book De Re Metallica, seen above.

No-one really knows for sure where the 18th century processing areas or stamp mill were, even though 904 tons were processed between 1758 and 1767. They could be buried underneath later buildings at the Bonsor Upper Mill, behind the Youth Hostel, or at the Red Dell Mill.

In the middle of the 19th century there were 3 processing mills at Coniston. Paddy End Mill and dressing floors were built specifically to process material coming from the levels dug around the Levers Water Beck. A larger complex at the Bonsor Mills, divided into Bonsor Upper Mill and Bonsor Lower Mill, was eventually to become the only place where ores were processed at Coniston.

Ore brought out along Deep Level headed to Bonsor Upper and Lower Mill. Gravity helped transfer it downwards, from one processing area to another before finally heading downhill to Coniston Village. At the Bonsor Upper and Lower Mills you can trace how the sequence of crushing and other processes travelled downhill through the terraces that make up the complex.

When the ore was brought out on the tramroad into the open air, it was dumped onto screens on the top terraces of Bonsor Upper Mill. Here it was sorted into three grades, boys and women smashing the large lumps with big hammers.

By 1842 semi-mechanical jigs had been introduced, and then later jigs that were fully powered by waterwheel. The new jigs were operated by children, but it was a significant improvement over jigging by hand which was considered to be one of the worst jobs. Waste from the jigs flowed away into a series of settling ponds. The settling ponds were emptied from time to time by ‘vanners’, who panned the ore using special shovels. This final process was improved at some point by passing the fine silts through a buddle, or sloping trough, several times.